Alison Harper Progression Statement 2012

From materialism to materiality: How can textile art and craft processes contribute to an ethical dialogue through an emerging materiality?

‘We live in a material world. Perhaps it is for this reason that materials are essential to sustainability ideas. Materials are the tangible synthesis of resource flows, energy use and labour; they make the invisible visible. They also connect us live and direct to the big issues of our times. Climate change, peak oil, overflowing land-fill sites and exploitative working practices can all be traced back, in some way, to the use, processing and demand for materials.’ (Fletcher,2010,p.3)

The opening statement outlines the main concerns of this investigation; the depletion of resources and what appears to be the wanton consumption of seemingly ‘disposable’ products. Developing from contemporary narratives and popular interest in environmental issues, this thesis intends to develop a dialogue between making and unmaking, of wasting and revaluing, and considers the ways in which consumers can renegotiate acts of consumption through creative and sensory processes, i.e. sight, touch, bodily movement. How can one measure and value objects if they are so easily discarded?

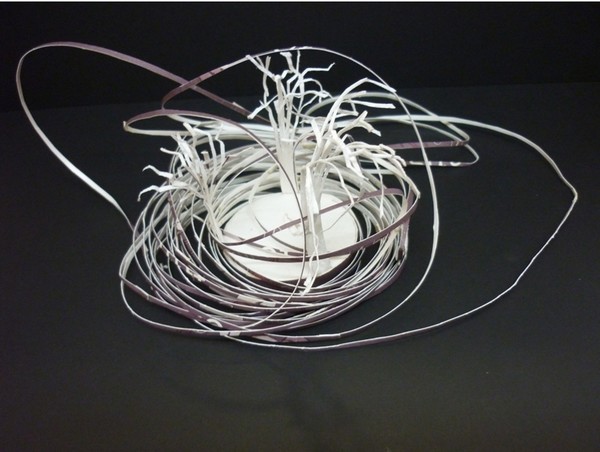

This research and my textile practice is about resources; I deconstruct, unpick, and rework mass produced ‘waste’ materials using ‘low-tech’ domestic techniques such as knitting, stitch, crochet. I am ‘rescuing’ these materials, giving them a new life, re-instating materials conveniently forgotten, obstinately re-inserting them back into the world with a new value and status; as art/craft objects demanding to be looked at again, to be reassessed via painstaking yet easily learned and culturally identifiable textile (and largely domestic and thus familiar) crafts practices.

I make work from materials that are usually taken for granted, used and discarded. Single use products; paper coffee cups, crisp packets, paper carrier bags; post-consumer waste that has nowhere to go. This is neither re-cycling nor up-cycling. This is more an exposure to the transformative qualities and alchemic power of craft, of making. For this investigation, making makes meaning and thus the ignored becomes the focus of attention, both for the maker (me) through the intensive deconstructing process, and for the consumer/spectator who identifies with the original ‘made’ and remade object. Here, valorisation references authenticity, novelty and the status of an object as ‘art’, whilst playfully referencing the carnivalesque, by which the low is elevated, albeit temporarily.

I make work from materials that are usually taken for granted, used and discarded. Single use products; paper coffee cups, crisp packets, paper carrier bags; post-consumer waste that has nowhere to go. This is neither re-cycling nor up-cycling. This is more an exposure to the transformative qualities and alchemic power of craft, of making. For this investigation, making makes meaning and thus the ignored becomes the focus of attention, both for the maker (me) through the intensive deconstructing process, and for the consumer/spectator who identifies with the original ‘made’ and remade object. Here, valorisation references authenticity, novelty and the status of an object as ‘art’, whilst playfully referencing the carnivalesque, by which the low is elevated, albeit temporarily.

‘There is so much to learn not only from the things we value but from the rubbish, detritus and discarded things.’ (Attfield,2000,xv) (Thompson,1979,p.35)

I believe that sustainability starts at our fingertips – the things we touch and use every day. Hence I am focusing on these materials of the everyday; plentiful and abundant in our privileged First World life-styles. We are normally distanced from these materials by a veil or shield of familiarity, a familiarity incurring disinterest and often a lack of recognition by the viewer. As Richard Sennett states ‘being able so easily to dispose of things desensitizes us to the actual objects we hold in hand.’ (Sennett,2008,p110)

I thus explore the properties of these materials, investigating their potential for renegotiation. How can I best articulate the materials, the waste, the methods of construction and deconstruction? How will I communicate environmental issues through one object in a way that will engage rather than patronise and thus alienate my audience?

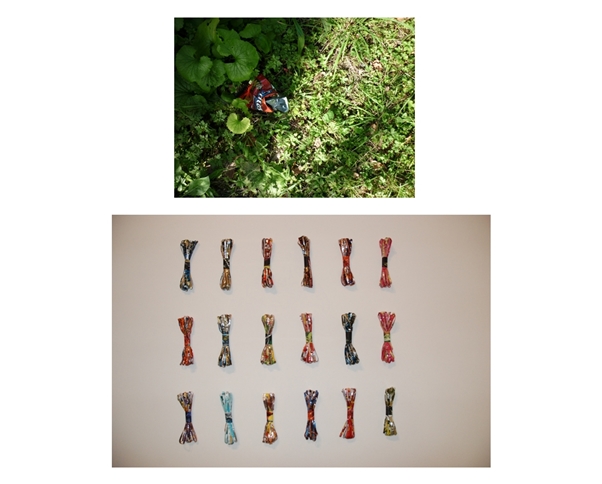

Indeed, this is a powerful and sensory process; a journey into the unknown; exciting and exacting. What will I find, discover, draw out of these objects? These materials have not been ‘pre-ordered’; I do not know what I am getting, what they can do, or rather what I can persuade them to do. This process is often begun by a serendipitous ‘finding’ of these things. They often are literally ‘found’ materials, having been discarded by the first user in unlikely places (particularly the crisp packets); on pavements, roads, footpaths; they are then discovered and retrieved by me, taken back to my workspace to begin their transformation.(Waldman,1992) Working with these materials assuages any ‘consumer guilt’ as I do not purchase them, am not creating a demand.

In order to make I first have to un-make; releasing material from these products. Un-making reminds us that a finished ‘object’ is not the end of the story; these materials do not go away. By using these processes this becomes the beginning, the narrative unfolding as I re-negotiate what these materials will become, re-negotiate the making process knowing that what results will bear the traces of its previous incarnation. I am taking away the ‘function’ of these objects and in so doing revealing the beauty of the materials, previously unseen. As Bugaeva notes in an analysis of the work of Santayana, our relationships with objects are born from systems of belief rather than specific and tangible truths. (Bugaeve in Ryder & Wilkoszewska,2004 p.137)

This investigative process of un-making draws on tacit knowledge; my skill as a maker, curiosity, empathy with the materials, a desire to create an aesthetic from these objects belying their industrial past. I want to draw attention to their continued existence despite them being no longer ‘useful’. I am demanding/seeking that these materials be given some kind of respect and consideration and by the same token am demanding/seeking respect for the craft processes and skills that have enabled me to re-invent and re-interpret them.(Coleman,1988)

Use of ‘the intelligent hand’; (Yanagi & Leach, 1989,p.108) feeling, in both senses of the word, listening, responding, feeling again, responding again in a different way,- perhaps engaged in a state of mind described by Sennett as ‘engaged material consciousness’, when in this state ‘we become particularly interested in the things we can change.’ (Sennett,2008,p120)

A further aim of my research is how I can take this argument further and propose that by engendering respect for this work and its methods could lead to a respect, an understanding of how things are made. Thus by recording and reflecting on my actions and also the responses of others this information will drive my research forward. Could it be that a better understanding of making processes would encourage an audience to consume less, to lose interest in mass-produced anonymous goods?

In seeking to elicit a response from the viewer I re-work these scavenged materials into different forms; paper cups are stripped bare to reveal a substrate of plastic; crisp packets are cut, stitched, made into yarn and fashioned into flowers, sometimes put back into the space vacated by the packet, an anonymous offering, turning what was once considered ‘rubbish’ into a ‘durable’ object, one which is valorised using a different set of rules. (according to Michael Thompson’s ‘Rubbish Theory’.) Thus I alter these familiar materials into unidentifiable ones; creating objects more permanent and aesthetically arresting; objects that on being ‘re-made’ are never the same, the uniformity in their previous existence has been erased by the attention of ‘the intelligent hand’. The educationist P.Ballard in a Dryad booklet from 1929 associated the teaching of handicrafts with ‘a certain sensitiveness to the great things in life; a certain sympathy with the aspirations and achievements of the human race. Above all it means a creative power, a capacity to do things.’(Ballard,1929,p.3) This continues the ethos of the Arts and Crafts Movement and particularly the teachings of C R Ashbee, who founded the Guild & School of Handicraft in 1888 in London’s poverty stricken Whitechapel, later moving it to Chipping Camden in the Cotswolds where it became an idealistic community, attempting to find an ethical balance between craft and commerce.

I am seeking a reaction; intrigue, amusement, surprise, engagement, curiosity. A principal aim is to show just how much material is implicit in these products. I can make between five and six metres of yarn from one crisp packet; a sheet of paper from the stripped paper of one coffee cup; fourteen metres of paper/plastic yarn from one cut cup.

I am seeking a reaction; intrigue, amusement, surprise, engagement, curiosity. A principal aim is to show just how much material is implicit in these products. I can make between five and six metres of yarn from one crisp packet; a sheet of paper from the stripped paper of one coffee cup; fourteen metres of paper/plastic yarn from one cut cup.

What is it? What is it for? Where has it come from? What have you done to it? Why have you done this? How have you done this? Where is it going to? Why bother?

The responses to the above questions will inform my methodology for the next part of my research. I need to unpick this process of ‘sensitisation’, if you like, to materials and to their provenance, what is it that makes people interested and keeps their attention.

These are some of the questions I hope will be engendered through engaging with the work. By using these familiar textile processes, processes that people have often experienced, most people have either knitted themselves, for instance, or seen other people doing so, makes the work more accessible. People are keen to know how I have done this and why – resulting conversations are often informative and environmental issues can be talked about in an unthreatening and light-hearted way.

The artist and sculptor Shane Waltener often uses his work as a way to engage people with art, these are frequently textile-based; sometimes knitted, sometimes stitched, sometimes just knotted, and result in large ‘free-form’ installations. He facilitates a process of ‘crafting’ together in order to allow for cultural and social histories relating to these crafts to be exchanged. Similarly in my practice conversations turn to how knitting was, and sometimes still is, used as a ‘thrift’ craft – the knitting of dishcloths, for example, the hours spent in unpicking and the re-working of worn knitted garments. In the current economic climate the notion of thrift has become popular and is subjected to a modern re-working; definitions of current ‘thriftiness’ would vary widely from war-time thriftiness, for example, when corners of teatowels were re-inforced prior to use so that in hanging them up the edges would not be worn. This re-inforces our current changing relationship with ‘waste’; what exactly is it, if something has any ‘use’ at all, should it be ‘saved’, collected, cherished?(Rowley,1997,p76)

Thus these products, mass produced in their millions and then discarded as a necessary by-product of consumerism and seen as having no value, neither monetary nor aesthetic, are re-invented and re-instated. By ‘installing’ these materials back into the public domain I am questioning attitudes to our treatment of ‘debris’ and to our dis-connection from not only the materials, but also from the life-cycle of ‘stuff’ and its inherent environmental impact.

By investigating the materiality of these products I am seeking a shift in current attitudes and am asking the question when does ‘insignificant’ debris become ‘significant’? When do we start to care?

(Crisp packets are made from plastic backed aluminium foil. There is a reason scientists call aluminium ‘congealed energy’; aluminium smelting requires more energy than any other metal processing on earth. (Leonard,2010,p82)

Walkers UK factories produce 10 million packets a day – satisfying just under half this country’s appetite for crisps. It is estimated UK consumption is 6 billion packets per year.)

www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2010/sep/01

Participative Projects

Knitting Chair

Running alongside and in some ways an antithesis to it, the other part of my practice involves collaborative/participative projects. I have taken my ‘knitting chair’ to various venues and invite people to join me in my making – knitting and crocheting yarn made from discarded crisp packets. I knit and unpick, emphasising the fact that this material never goes away, it has nowhere to go, being neither bio-degradable nor re-cyclable. As stated people often do not recognise these materials – something I find fascinating as this shows a seeming disconnection from the physical world, of what things are made of and hence their material properties. The objective is to remove thrown away objects from the bin and return them to consumers in new and unexpected forms. Likewise, textile craft processes are taken ‘out of the closet’, subverting their domestic heritage by transforming the unhomely (discarded waste) with homely modes of manufacture. Simple textile processes are employed as a way to engage an audience, engender an interest in textile based making and to have fun. These activities always include discussions of the

Running alongside and in some ways an antithesis to it, the other part of my practice involves collaborative/participative projects. I have taken my ‘knitting chair’ to various venues and invite people to join me in my making – knitting and crocheting yarn made from discarded crisp packets. I knit and unpick, emphasising the fact that this material never goes away, it has nowhere to go, being neither bio-degradable nor re-cyclable. As stated people often do not recognise these materials – something I find fascinating as this shows a seeming disconnection from the physical world, of what things are made of and hence their material properties. The objective is to remove thrown away objects from the bin and return them to consumers in new and unexpected forms. Likewise, textile craft processes are taken ‘out of the closet’, subverting their domestic heritage by transforming the unhomely (discarded waste) with homely modes of manufacture. Simple textile processes are employed as a way to engage an audience, engender an interest in textile based making and to have fun. These activities always include discussions of the

The topic of how much time this has taken me is one that is often brought up by the viewer – it seems that in a ‘time-poor’ culture these ‘time-rich’ activities raises questions of how we spend our time and what are ‘worthwhile’ activities; these having no obvious monetary gain or exchange value; saying some-one has ‘too much time on their hands’ is intended as a form of derision. (Turney,2004)

The use of textile art and craft processes used in this work, processes traditionally associated with making and mending, caring and sharing and the use of tactile ‘soft’ materials, serves to underline and emphasise the current feeling of alienation from the physical world and dissatisfaction with our commodified culture. With new technologies changing our lives almost on a daily basis, we are in danger of living in a world where often little is understood of how things are made; where they have come from; whether they will always be there or indeed what went before. I am also stressing the importance of remembering that the maintenance and nurturing of skills, of knowing how to make things and the inherent curiosity about and fascination with materials is viewed as an important part (not always recognised) of being human, sensitive, of being creative, of connecting with ourselves and with society, of being compassionate.(Johnson,1997,p.292)

Pompom Project

The pompom project was another project that involved an audience by introducing them to a simple textile skill- a simplified way to make pompoms. I was intrigued at the way that this was so enthusiastically taken up by people as it seems that almost everyone had memories of making pompoms at school. Thus it seemed to tap into a nostalgic view of craft and of craft-making, similar to knitting, that had been learned in childhood. This project was a delight as it became a way to involve and engage people, the resulting ‘yarnpommed’ tree outside the Brewhouse in Taunton becoming part of the Textile Forum South West’s exhibition ‘Mapping the Future; Where Are You Now?’ This project started as an idea and was taken up by others, including Sue Prichard, curator of contemporary textiles at the V&A Museum and taught me a lot about the potential power of textiles to involve, break down barriers and incentivise both on an ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ level.

David Gauntlett emphasises the importance of creativity as ‘doing’, an act of agency rather than an end product. ‘Creativity might be better understood as a process, and a feeling. In this way of looking at it, creativity is about breaking new ground, but internally; the sense of going somewhere, doing something that you’ve not done before. This might lead to fruits which others can appreciate, but those may be secondary to the process of creativity itself, which is best identified from within’. (Gauntlett,2011,p17)

In ‘Making Is Connecting’ Gauntlett is adding to the current upsurge of interest in making and craft as a response to our contemporary world of digital technology. By making, as Gauntlett and others suggest (Johnson) we are engaging with the world in a different way, not as consumers of culture and products but as participatory interactive ‘agents’, engaging with materials and with each other.

The philosopher Isis Brook discusses how it is possible to discover a sense of place through making; she presented her paper ’Craft Skills and their Role in Healing Ourselves and the World’ at the first Making Futures conference in 2009. The paper ‘came out of a concern about placeless environments as unconducive to human flourishing’ and argued that ‘Alongside the historical shift to placelessness there has also been a move away from engagement with matter’ but put forward powerful ideas of how in making ‘the world comes close’, of the ‘self transformatory power of working with matter in an engaged way’ and of the search for ‘more enriching ways of living’.

In discussing definitions of materialism and what it means to be materialistic she says ‘we can endorse or promote a ‘new materialism’ that really is about engaging with matter. Even if I live in a placeless environment if I can be encouraged to just engage with matter I will be forging a new connection to where I am at the micro level of sitting here doing this and at the macro level of engaging with the material world with its attendant limits and balances’. http://makingfutures.plymouthart.ac.uk/journalvol1/papers/brook-isis.pdf

My practice sits on the boundary between ‘professional’ practitioner and ‘amateur’ maker; drawing on the traditions of generations of knitters, sewers, quilters; of skills passed down and remembered. A realisation that unless practiced these skills will disappear needs to be encouraged and the plethora of craft books, craft based websites and networks, the popularity of celebrities such as Kirsty Allsop’s recent nostalgic foray into the celebration of ‘the handmade’ would seem to underline this enthusiasm.

Craft+activism=craftivism

There have been many forms of political engagement using textile processes from the quilts of the 18th century, to the banners of the suffragists and women protestors knitting at Greenham Common (Parker). The early 2000’s saw a resurgence of interest/activity which uses the internet as a means by which to communicate, activate, and inform a new younger generation of ‘craftivists’ (Turney; etc). There are many innovative, subversive and thought-provoking projects instigated by textile artists, often knitters, who are providing a platform for alternative forms of protest. The artist Cat Mazza founded the anti-sweatshop website Microrevolt; she involved over 500 knitters from around the world to produce a blanket depicting the Nike logo, this was used as a kind of ‘petition’ to support the low paid workers employed by the company. The Canadian artist Barb Hunt uses the conventional gallery space to show her work; her beautifully made and displayed series of knitted landmines emphasises the tension and altered meaning between the crafted objects and the man-made (no pun intended) ones, resulting in a powerful anti-war statement. (See also Lisa Anne Auerbach, Marianne Jorgensen, Adrienne Sloane, Laurel Roth)

Craftivism by its nature appears unthreatening, its efficacy difficult to measure, but as Kirsty Robertson states ‘………textiles are again at the forefront of a politicized praxis, ranging from anarchist knitters braving the tear gas at mass protests to a widespread resurgence of knitting in public, and from global anti-sweatshop actions to artists using handwork, often knitting or embroidery, to push the boundaries of the global art world.’(Buszek,2011,p.185-186)

My work has a more direct link with environmental issues due to the materials I am using, which serves to re-enforce this message, than an almost ‘once-removed’ passive activity of making in order not to consume, which is the rationale, realised and acknowledged or not, behind some forms of craftivist activity.

‘Craftivist practices share common ground with the DIY aesthetic and its political roots. Ideas concerning the use of craft practices as political tools are again circulating within the growing indie craft movement, where handcrafted (and often locally produced) items are championed as alternatives to mass-produced, globally distributed goods.’ (Buszek, 2011, p21)

Betsy Greer describes her realisation of how exploring her creativity impacts on her desire to make the world a better place.

‘This new way of thinking . . . . . was my indoctrination into the world of the do-it-yourself (DIY) ideology and activism. By using my own creative drive as a positive force instead of allowing the wheels of consumerism to direct me, everything I did became part of my activism. Instead of pitting myself against others . . . . I finally felt free to explore my own creativity and identity.’(Greer,2008 p.10) and

‘For a time I considered anything even vaguely resembling the domestic arts to be completely disconnected from my creative path. But I found that . . . . Knitting didn’t make me a traitor to feminism; instead I found myself able to connect with women of previous generations in a whole new way and celebrate their accomplishments.’ (ibid. p12)

It can be hard to connect these activities with changing society but as Shannon Stratton states ’Whether or not the popularity of hobby-craft provides wide-spread evidence of a general, conscious interest in slow-activism is debatable, but the surge of interest in needlecraft as a means to foster community and as a vehicle for political expression is notable.’(Gustafson,Gogarty,2007,p48) And ‘It is certainly too generous to claim that all knitters are engaged in political activity directly through their handicraft, but the mark of a subversive activity – seeking to undermine the power and authority of an established system – depends on whether or not it can subvert hierarchy, specialization, and non-communication. In a capitalist culture, subverting that system requires the redirection of energy away from the (direct or indirect) production of capital.’ (ibid.p.47-48)

My work has a more direct link with environmental issues due to the materials I am using, which serves to re-enforce this message, than an almost ‘once-removed’ passive activity of making in order not to consume, which is the rationale, realised and acknowledged or not, behind some forms of craftivist activity; a subject I have discussed at conferences and in print (abstract below.) Here I stress the ‘ethical values’ inherent in traditional textile craft practice; of thrift and innovation and making with love, of mending and making, not making do.

‘Craftivist practices share common ground with the DIY aesthetic and its political roots. Ideas concerning the use of craft practices as political tools are again circulating within the growing indie craft movement, where handcrafted (and often locally produced) items are championed as alternatives to mass-produced, globally distributed goods.’(Buszek,2011,p210)

Summary

Since commencing this research and investigating these issues I look at things differently, even though I would have considered myself to have been ‘environmentally aware’ before. I have become aware of developing a ‘questioning of materiality’ if you like, – a questioning of where things have come from, how they got there? After all, all material goods have been ‘designed’, fashion, food, etc., can all be scrutinised and ‘unpicked’ metaphorically. I question their provenance; where have they come from, what materials have been used, what has been their impact on the environment and also on the people who made them, what was the emotional as well as monetary impact. This can be seen as part of a general societal change as is demonstrated in the popularity of farmers markets and supermarket initiatives to tell you which cow your cheese comes from.

In essence, this project establishes narratives that discuss and reflect on the role of craft, of making (and remaking) in a consumer society.

Milestones Achieved

Work selected for Material Actions Exhibition

Material Actions was an exhibition of textile art inspired by ideas explored in the Textile Forum South West Conference ‘Textile Footprints’, this had taken place in March 2009 and was a timely look at issues surrounding the ethical, ecological and sustainable use of materials. This toured to Centre for Contemporary Art in the Natural World, Haldon Forest Park, Exeter, the Create Centre, Bristol and Bath School of Art and Design.

Abstract accepted and paper presented at Making Futures II Conference, Dartington Hall, Devon, September 2011

Invited attendee at Connecting Craft and Communities workshop, University of Exeter action research project, September 2011

Work selected for Papier Global Exhibition, Deggendorf, Germany, April 2012

Future Milestones

Development of an informed web presence; develop a blog, should be engaging yet scholarly, can be used as a resource, through links and information sharing. Use it to initiate projects, share ideas. To develop this as a methodological tool to record/measure, reflect and respond to work produced, that can be applied to the work of crafts practitioners in general.

Documentation needs to be more thorough and considered through web/blog and recording. To record a narrative of remaking, that is determined by materials, but also by reflections and responses.

Find—————————Record

Unpick————————Record

Remake———————-Record

Replace———————-Record

Reflect

Re-evaluate

To continue to develop my practice; critique the world through my practice.

Production of a publication/film/exhibition.

Bibliography

Exhibitions visited

Radical Nature; Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet, Barbican London July 2009

Taking Time; Craft and the Slow Revolution, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Nov. 2009

Craftivism, Arnolfini, Bristol, Jan 2010

Bauhaus; Art as Life, Barbican, London, May 2012

The Age of Oil, Bridport Arts Centre, Dorset, May 2012

Conferences attended

Making Futures: the crafts in the context of emerging global sustainability agendas Edgecumbe Mount Plymouth September 2009

Material Evidence, co-organiser Corsham Court, Wiltshire September 2010

Transnational Clothing, Bath School of Art and Design, paper presented, September 2011

Internet of Things Lab, Watershed, Bristol, Crafts Council research seminar November 2011

Textile Research In Progress (TRIP) Conference, Loughborough University, November 2011

Outside: activating cloth to enhance the way we live, Huddersfield University, Yorkshire January 2012

Material Actions Seminar, Bath School of Art and Design, co-organiser February 2012

Introduction to participating artists’ on-line conversation for Material Action exhibition.

‘It is fitting that at a time of financial and political upheaval there should be a re-assessment of values, environmental relationships and the motivating forces prevalent within our society. The pressures and implications of globalisation, the questioning of the uses of resources and the increasing economic divisions between different sectors of society make the focus of this exhibition all the more timely. Textile artists traditionally work with process and materials intrinsic to everyone’s lives. This exhibition shows how the artist represented are responding to these challenges through their work and shows a cross-section of thought-provoking and challenging work which will engage and intrigue audiences more used to seeing textiles as non-provocative form of expression.’

Connecting Craft and Communities, Dartington Hall, Devon September 2011 University of Exeter research seminar ‘Crafting Sustainability and Well-being’ brings together two key agendas for contemporary society: the challenges of building a sustainable future and the challenge of building/maintaining resilient communities that offer significant advantages in terms of the improved well-being, health and life chances

Making Futures ll, Dartington Hall, Devon September 2011

‘ As we negotiate these pivotal times which are testing our values and questioning rates of consumption, the artist’s and maker’s voice and activism makes an important contributions to thinking through the future.’

‘ But the fact remains that our understanding of the interactions between the contemporary crafts and the modern environmental and sustainability ‘movements’ remains largely uncharted, unrepresented and under-theorised.’

‘Sustainability and environmental activism and the crafts; for example, contemporary crafts practice as a means to empower self and others to gain critical awareness of the habitat, to engage in grassroots activism and community participation. Also, possible blending between the digital media technologies used to give voice and empower activists, and the crafts.’ http://online.plymouthart.ac.uk/micro-sites/conference/index.php?page=Conference-Themes&pag_id=1

Abstract for paper presented;

Responses, redefinitions and repositionings

Creativity as a new direction in eco-philosophy

More ‘re’ words

I have framed this paper and my current research thinking into a series of seven‘re’ words.

Using these words implies a ‘doing again’, a dis-satisfaction with what has gone before, a feeling of things not being right.

These are my seven words:

1. Revolution

The movement known as ‘craftivism’ has been described as a craft revolution; this initially seems to be a contradiction in terms as revolutions can often be violent and brutal, as recently seen. This paper examines the incongruity between the (relatively) new found popularity of textile craft processes and the use made of web-based social networking sites resulting in a powerful movement which promotes anti-capitalist, anti-war and environmental and sustainability messages, resulting in a ‘revolution’, but not as we know it.

2. Researching

My own work is currently based around a practice-based Phd; researching ways in which textile art and textile craft processes can contribute to a dialogue between art, materials and social and cultural change.

3. Resources

The current use, or rather mis-use of resources play an important part in my work; I re-examine, re-evaluate and re-configure materials usually taken for granted and discarded.

4. Reflecting

Low-tech textile craft methods leave space and time for reflection, thinking and perhaps a little dreaming. In a consumer driven culture that expects us to be busy and productive, the act of making ‘just for the love of it’ becomes a political act, subverting notions of ‘exchange value’ necessary to sustain a capitalist system.

5. Reconnect

What is the meaning of making in the twenty first century; why do we need it; what is its relevance?

Is there a current feeling of disillusionment with our ‘commodified’ culture?

How do we reconnect with ourselves, with each other and with society?

I will be looking at David Gauntlett’s book ‘Making is Connecting’ (Gauntlett, 2011) where he discusses the social meaning of creativity from DIY and knitting to You Tube (www.youtube.com) and Web 2.0

6. Remix

According to Lawrence Lessig a ‘remix’ culture is one where people are free to add, change, influence and interact with their culture. In his 2008 book ‘Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy’, he describes how we could and should use technology to benefit those who make and consume art. This process is facilitated by the use of Web 2.0, making it an adaptable medium for participation with craftivism initiatives/websites and a perfect platform for the dissemination of ideas and information.

7. Redefinition

At a time of economic and societal unrest and uncertainty new paradigms are needed and answers to the question of how the role of artists and practitioners can be redefined for the twenty first century.

How can we define these positive changes, search for a different set of values, a new form of ‘eco-philosophy’ with creativity at its heart, which can sustain us for the future?

Talk/workshop Centre for Contemporary Art in the Natural World – Aviva Rahmani, American environmental artist

Talk/workshop Centre for Contemporary Art in the Natural World -Shelley Sacks, Artist and director Social SculptureUnit Oxford Brookes University CCANW

‘Central to the field of social sculpture is a social understanding of work and a re-definition of wealth that emphasises the well-being of the whole, our creativity and our work for each other. Although we still live in a society in which work is rewarded with money and we all need money to live, a viable society will be one in which we work for the benefit of ourselves and others, and reward for this work takes a very different form.’ Shelley Sacks

Therapeutic Knitting – one day event organised by Stitchlinks involving medical practitioners, health workers etc. BRLSI Bath June 2012

An underlying premise of these activities is that if people feel empowered through their own creativity they are likely to make more and consume less. ‘Craft’ becomes a more current, relevant, purposeful place.

‘Globally people are using about twenty five per cent more natural resources than the planet can replace. In the UK we’re consuming three times our fair share of the planet’s natural resources. In the western world we live and consume as if we have three planets at our disposal instead of one.’ (ww.wwf.org.uk)

Websites

www.greenmuseum.org

www.adbusters.com

www.slowtextiles.org

craftresearchblogspot.com

textilesenvironmentdesignblogspot.co.uk

faythelevine.com

handmadenationthemovie.com

making a slow revolution.wordpress.com

craftivist-collective.com

Journals

Sublime

Resurgence

Selvedge

Crafts

Literature

Craft

Adamson, Glenn, thinking through craft, Berg, 2007

Attfield, Judy, Wild Things; the Material Culture of Everyday Life,Berg,2000

Ballard P. The Cultural Value of Handicraft , Dryad, 1929

Brook, Isis, Craft Skills and their Role in Healing ourselves and the World, Making Futures conference paper, 2009

Buszek, Maria Elena, ed. Extra/Ordinary Craft and Contemporary Art, Duke University Press, 2011

Coleman, Roger, The Art of Work: An Epitaph to Skill, Pluto Press, 1989

Crawford, Matthew, The Case for Working with Your Hands or Why Office Work is Bad for Us, Penguin Group, 2009

Dormer, Peter, ed. The Culture of Craft, Manchester University Press, 1997

Fletcher, Kate, Material Actions Exhibition Catalogue, Plymouth College of Art Press,2010

Frayling, Christopher, On Craftsmanship towards a new Bauhaus, Oberon Books, 2011

Gauntlett, David, Making is Connecting, Polity Press, 2011

Greenhalgh, Paul, ed. the persistence of craft, London, A & C Black, 2002

Greer, Betsy, Knitting for Good, Trumpeter Books,2008

Gustafson, Paula, Gustafson, Nisse, Gogarty, Amy, eds. Craft Perception and Practice, Volume lll, Canada, Ronsdale Press, 2007

Harrod, Tanya, ed. Obscure objects of desire, Great Britain, Crafts Council, 1997

Hemmings, Jessica, ed. In the Loop Knitting Now, Black Dog Publishing, 2010

Hung, Shu, Magliaro, Joseph, eds. By Hand, the Use of Craft in Contemporary Art, Princeton Architectural Press, 2007

Johnson, Pamela, in Harrod ed. Obscure Objects of Desire, Crafts Council, 1997

McFadden, David Revere, radical lace and subversive knitting, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Arts and Design, New York, 2007

Moore, Mandy, and Prain, Leanne, Yarnbombing The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2009

Murphy, Bernadette, Zen and the Art of Knitting, Adams Media, 2002

Risatti, Howard, a theory of craft, function and aesthetic expression, University of North

Carolina Press, 2007

Rowley, Sue (ed.) Craft and Contemporary Theory, Allen & Unwin, 1997

Ryder, John and Wilkoszewska, Krystyna, eds. Bugaeva,lyubov, Deconstruction and Reconstruction, Rodopi, 2004

Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, Allen Lane, 2008

Stoller, Debbie, Stitch ‘n Bitch Nation, Thomas Allen & Son, 2004

Turney, Joanne, Here’s One I Made Earlier, Journal of Design History,2004

Turney, Joanne, The Culture of Knitting, Berg, 2009

Waldman, Diane, Collage, Assemblage and the Found Object, H.N.Abrams, 1992

Yanagi, M. and Leach, B., The Unknown Craftsman, Kodansha Publishing, 1989

Environment

Carson Rachel, Silent Spring, Penguin Books, 1962

Leonard, Annie, The Story of Stuff, Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2010

Girling, Richard, Rubbish, Transworld Publishers, 2005

Hoskins, Rob, Transition Handbook, Green Books Ltd, 2007

Mcdonough, William and Braungart, Michael, Cradle to Cradle Remaking the Way We Make Things, Rodale Press, 2003

Papanek, Victor, the Green Imperative, Thames & Hudson, 1995

Stevenson, Mark, An Optimists Tour of the Future, Profile Books, 2011

Roszak, Theodore, Gomes, Mary E. eds. Ecopsychology, Restoring the Earth Healing the Mind, Sierra Club Books, 1995

Thompson, Michael, Rubbish Theory;The Creation and Destruction of Value, Oxford University Press, 1979

Other

Miller, Daniel, A Theory of Shopping, Polity Press, 1999

Miller, Daniel, The Comfort of Things, Polity Press, 2008